Before anyone asks, yes, this is the same research brain at work. The historical gaps, suppressed records, long-term power structures, and inconvenient facts that fueled the conspiracies in The Fablecastle Chronicles are the very same ones that led me into the BRICS framework and the geopolitical realities behind A New Dawn.

While developing A New Dawn, I did not begin with ideology or messaging. I began with research. Specifically, I was examining the structural forces behind the BRICS objectives and why nations outside the Western capitalist framework are increasingly willing to challenge a U.S.-dominated global order.

What emerged was not a theory. It was a pattern.

A New Dawn lives under the banner of truth in fiction. The plot may be fictional, but the systems that drive it are not. China’s economic rise, its resistance to capital-driven governance, and its long-term strategic posture form a real-world foundation that directly informs the geopolitical tensions at the heart of the novel.

The story works because the underlying power dynamics are real.

Food, Stability, and the Fear of Collapse

One of the quiet truths embedded in A New Dawn is that governments that fail to meet basic human needs eventually lose legitimacy. This idea did not come from imagination. It came from history and observation.

When I traveled to China in the late 1990s, food was cheap and widely available. This was intentional. China learned long ago that starving populations rebel. Food security is not treated as a market outcome but as a political necessity.

In A New Dawn, this same principle underlies global instability. When systems prioritize profit over survival, unrest becomes inevitable. The novel’s conflicts do not erupt because of ideology alone but because material conditions make collapse unavoidable.

Capital Without Control Is the Antagonist

At its core, A New Dawn is not simply a political thriller. It is a systemic one.

China’s model demonstrates that capital can exist without controlling politics. Western corporations operating in China learned this quickly. Even in the 1990s, when China hosted the world’s largest Kentucky Fried Chicken, those corporations operated under state authority. They paid fees. They followed the rules. They did not bribe officials because capital does not dictate policy to the Politburo.

In A New Dawn, the central threat emerges from the opposite condition. A system where capital dictates elections, policy, media narratives, and regulatory enforcement. The antagonistic force in the novel is not a single villain but a structure where money replaces governance.

That structure is recognizably American.

Social Equality as a Counterpoint

There is a quiet scene in my memory that shaped how I wrote power dynamics in A New Dawn. I watched a Chinese businessman stop to pick up a dropped cup and hand it to an elderly woman sweeping the street. No hesitation. No hierarchy. No transaction.

That moment mattered.

In the novel, dignity is a recurring theme. Who is seen? Who is disposable? Who is protected? Capitalist systems tend to assign value based on utility and profit. China’s model, for all its flaws, rejects that premise at the social level in ways that are rarely acknowledged in Western narratives.

The contrast sharpens the moral tension in the book.

Knowledge as Power and the Long Game

China’s rise was not built on charity or accident. Cheap labor was offered to Western corporations in exchange for something far more valuable than wages. Knowledge.

Manufacturing expertise, logistics systems, engineering processes, and industrial scale were absorbed deliberately. China understands that knowledge is power.

This principle directly informs A New Dawn. The struggle in the novel is not merely about resources or territory but about who controls information, systems, and long-term planning. Those who chase short-term profit lose. Those who think in decades survive.

This is not speculative fiction. It is an observation sharpened into a narrative.

Truth as a Weapon

China teaches American history without mythology. Slavery, indigenous displacement, corporate exploitation, and imperial violence are not hidden. This truth is used strategically to expose hypocrisy and weaken moral authority.

In A New Dawn, truth functions the same way. The most destabilizing force in the story is not violence but exposure. When systems built on narrative control are confronted with reality, they fracture.

That idea comes directly from watching how truth is deployed geopolitically in the real world.

Quiet Strength and the BRICS Undercurrent

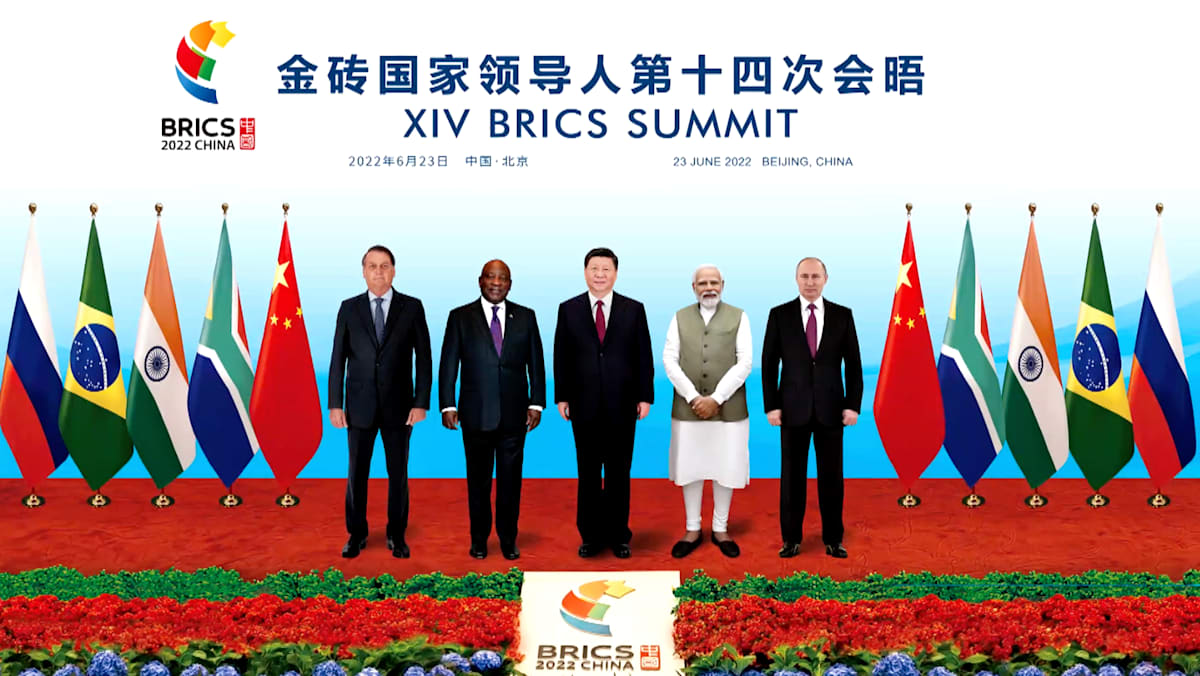

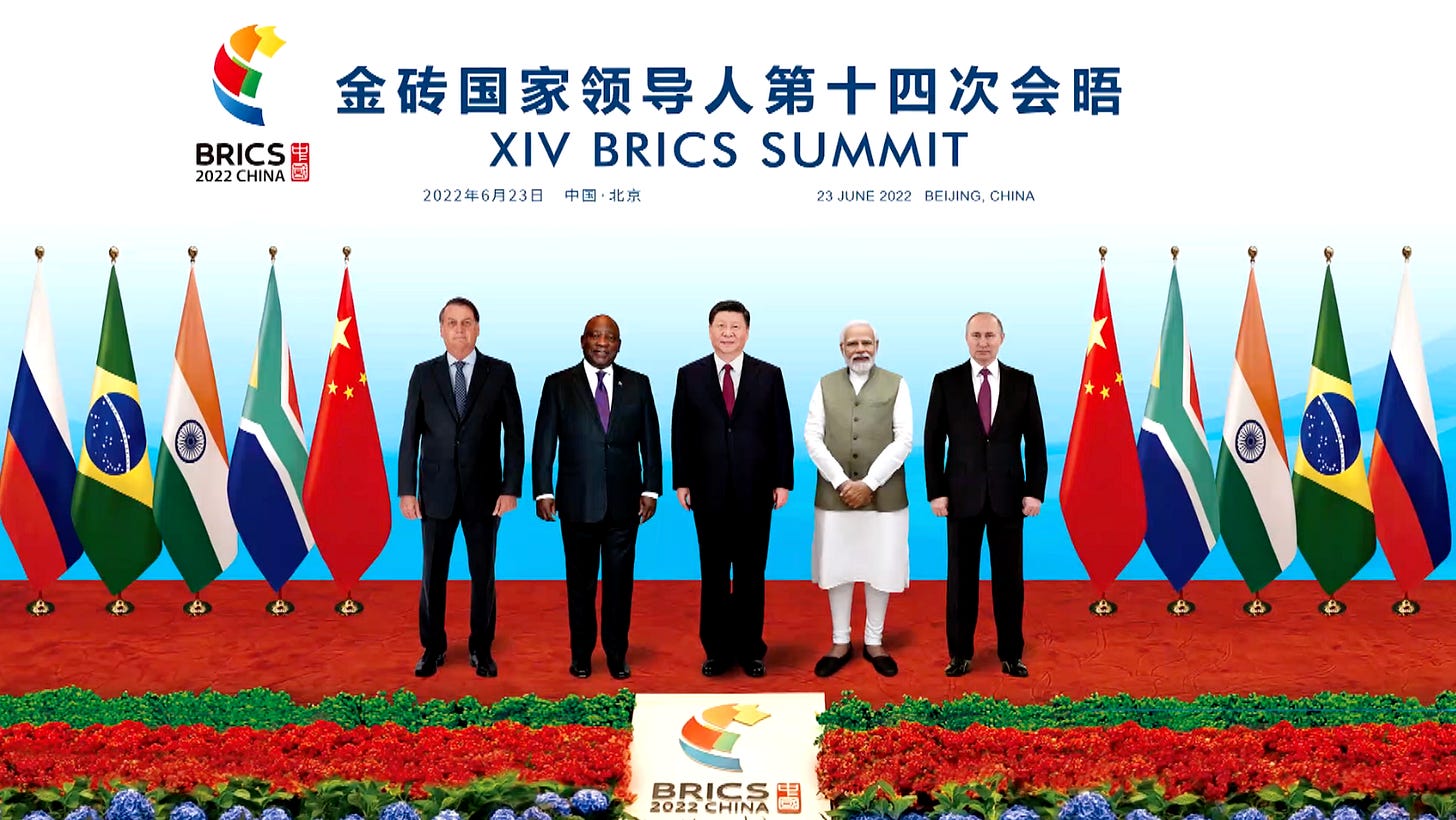

The BRICS framework that informs A New Dawn is not about domination. It is about insulation. Long-term planning. Reducing exposure to capital-driven volatility.

China’s ability to execute decades-long strategies under Xi Jinping is not an endorsement of authoritarianism in the novel. It is a recognition that systems insulated from capital pressure behave differently from those owned by it.

The United States, by contrast, is portrayed as reactive, fragmented, and captured by money. Not because Americans are worse people, but because capital controls the machinery of governance.

Why A New Dawn Feels Uncomfortably Real

Readers often say A New Dawn feels plausible to the point of discomfort. That is intentional.

The novel resonates because it does not predict a future. It is describing the present through a fictional lens. The power struggles, the institutional decay, and the geopolitical recalibration are already underway.

China’s model is not presented as flawless or aspirational. It is presented as disciplined, patient, and structurally resistant to capital capture. That resistance is the fault line running through the book.

A New Dawn is fiction built on fact.

The systems are real.

The stakes are real.

Only the characters are invented.

And that is what makes the story impossible to dismiss.

Key Takeaways

China’s Economic Model

- China operates a socialist market economy, not a capitalist one, markets exist, but the state controls strategic sectors and national direction.

- China became the fastest‑growing major economy and the world’s second‑largest by nominal GDP through state‑guided reforms, not laissez‑faire capitalism.

- The CCP’s model blends state ownership, centralized planning, and selective market reforms, rooted in Marxist‑Leninist principles adapted to China’s context.

Historical Foundations

- China’s early industrialization relied on Soviet‑style planning, heavy state ownership, and collectivized agriculture during the 1950s.

- The First Five‑Year Plan (1953–1957) built China’s heavy industry and placed two‑thirds of industry under state ownership.

- “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” emerged as a pragmatic adaptation of socialism to China’s historical and cultural conditions.

Why China Is Not Capitalist

- The Communist Party maintains a monopoly on political power, preventing private capital from influencing national policy.

- China’s system explicitly aims to guide market behavior, rather than allowing markets to guide the state.

- Strategic sectors, like energy, banking, telecom, and infrastructure, remain state‑controlled, ensuring capital cannot dominate national priorities.

Long‑Term Planning Capacity

- China’s Five‑Year Plans are the core mechanism for long‑term national strategy, enabling unified, multi‑decade development goals.

- The state uses planning to coordinate technology, industry, poverty alleviation, and modernization, rather than leaving these to market forces.

- This planning capacity is a defining feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics, enabling continuity across decades.

Corruption and Governance

- China has experienced major corruption challenges historically, especially during early reform periods.

- The CCP treats corruption as a systemic threat to socialist governance and has launched repeated anti‑corruption campaigns to preserve Party authority (implied across sources).

- Governance reforms emphasize strict Party discipline and centralized oversight to prevent capital from capturing the state.

Unified Political Structure

- The CCP’s centralized leadership ensures policy continuity, unlike capitalist democracies, where capital and elections shift priorities.

- The Party’s structure prevents millionaires or corporations from influencing the Politburo or national strategy (implied across sources).

- China’s political model is built on state unity, long‑term goals, and ideological coherence, not competition between capital‑funded interests.

References

Falk, Richard. “Was China’s Amazing Rise Due to Socialism with Chinese Characteristics or Capitalism with a Chinese Facade or a Little of Both?” Richard Falk, 23 Dec. 2021,

Lopez, Matthew. “Why China Isn’t Capitalist Despite the Pink Ferraris.” Spectre Journal, 2021,

https://spectrejournal.com/why-china-isnt-capitalist-despite-the-pink-ferraris/.

Naughton, Barry. The Chinese Economy: Adaptation and Growth. 2nd ed., MIT Press, 2018.

Xi, Jinping. The Governance of China. Foreign Languages Press, 2014.

World Bank. “Poverty and Equity Brief: China.” World Bank Group, 2020,

https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/brief/poverty-and-equity-brief.