Introduction: When the Camera Became King

But what if television had been part of the story from the very beginning? Lincoln’s brilliance likely still would have carried him, though not without risk. His gaunt frame and weathered face might have looked awkward on screen, but his piercing eyes, deep voice, and unmatched storytelling would have made him unforgettable in televised addresses. Andrew Jackson almost certainly would have become a star. His raw fire, defiant posture, and populist energy were made for prime time, though in a 24/7 news cycle, his volatility might have backfired, turning him from hero to cautionary tale. Jefferson, Madison, and Polk would not have been so lucky. Their long, intellectual speeches would collapse into flat soundbites, leaving them overshadowed by more forceful personalities.

In the glow of the camera, Roosevelt, Jackson, Kennedy, and Theodore Roosevelt would have risen even higher. At the same time, men like Buchanan, Fillmore, and Hoover likely would have faded into obscurity before history ever remembered them. And perhaps most unsettling of all, many of the men we call presidents might never have made it past the relentless scrutiny of the modern news cycle, where every gesture, every flaw, every stumble becomes a defining image.

It makes you wonder, not only about the past, but about the future. Television reshaped politics in 1960, but what about the platforms that dominate today? Would Washington’s dignity survive the instant outrage of Twitter? Would Lincoln’s wit cut through the meme wars of Instagram? Would even Kennedy, the first TV star-president, withstand the endless dissection of mainstream media? As we look back at the presidents who might have thrived or failed on television, we are really asking a bigger question. How much does technology shape leadership itself?

The Founders on Film: Gravitas Meets Awkwardness

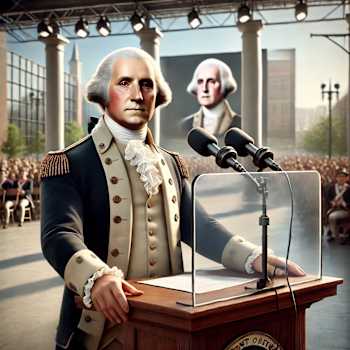

George Washington (1789–1797) would have been a natural for television. His towering height and commanding presence projected authority into every household. Imagine the first televised inauguration, with Washington’s hand trembling slightly on the Bible while his sheer gravitas silenced the nation.

John Adams (1797–1801) was brilliant and fiery, but his stout build and quick temper might have alienated audiences. Picture him snapping at a reporter’s question during a live broadcast, his legacy rewritten not by his intellect but by his short fuse.

Thomas Jefferson (1801–1809) was a visionary thinker, yet his soft-spoken nature might not have survived the studio lights. A Jefferson–Hamilton debate on television could have been decisive. Jefferson droning through theory while Hamilton leaned into the camera with sharp, quotable lines that dominated the tavern talk for weeks.

James Madison (1809–1817) stood only five feet four inches and was deeply reserved. Imagine him lost in the shadow of towering political rivals, struggling to project his brilliance past the glow of the camera.

Expansion Era: Heroes and Forgettables

James Monroe (1817–1825) had soldierly dignity, but television would have exposed how little charisma he possessed.

John Quincy Adams (1825–1829) was intensely cerebral and combative but awkward in manner. He might have been the type to scowl during live coverage, turning off voters no matter how sharp his arguments were.

Andrew Jackson (1829–1837) was fiery, scarred from battle, and brimming with raw energy. Picture him storming off a debate stage, spinning back toward the lens and daring his opponent to settle it outside, a moment that would have gone viral in any age.

Martin Van Buren (1837–1841) was urbane and polished but slippery in reputation. On television, his smooth delivery might have looked more like scheming.

William Henry Harrison (1841) carried a folksy war-hero appeal that played well in campaign rallies. Imagine his “Log Cabin and Hard Cider” campaign reimagined as the first televised political ad, with Harrison drinking cider by the fire, winning hearts just before his presidency was cut short.

John Tyler (1841–1845) looked distinguished, but the camera would have emphasized his lack of spark.

Pre-Civil War Politicians: Style, Strength, and Stumbles

James K. Polk (1845–1849) was stern and driven, but his intensity might have appeared abrasive on television.

Zachary Taylor (1849–1850), “Old Rough and Ready,” would have looked rugged and relatable, the kind of leader television could turn into a folk hero despite his unpolished style.

Millard Fillmore (1850–1853) was bland and forgettable, and television would have made him invisible in a race against bolder personalities.

Franklin Pierce (1853–1857) was handsome and eloquent. On screen, his good looks might have carried him further than his policies ever did.

James Buchanan (1857–1861) was indecisive and uninspiring, qualities that would have been painfully clear under the glare of cameras.

Lincoln and Beyond: The Civil War and Reconstruction Era

Abraham Lincoln (1861–1865) was awkward in appearance but piercing in presence. Picture him seated in a studio with lamplight behind him, pausing mid-speech before leaning into the camera. For a moment, every viewer in the country feels as though Lincoln is speaking directly to them.

Andrew Johnson (1865–1869) was combative and defensive. Under live broadcast, his rants might have defined him, alienating the very audiences he sought to win.

Ulysses S. Grant (1869–1877) was revered as a war hero but quiet and laconic. Imagine a campaign ad showing him standing silently with his medals, while a narrator does the talking—powerful as imagery, less so in person.

The Gilded Age: Style Versus Substance

Rutherford B. Hayes (1877–1881) was respectable but lacking in charisma. He likely would have faded into the television background.

James Garfield (1881) was intelligent, articulate, and moral, a natural for televised addresses. Had cameras broadcast his speeches, his assassination might have been felt in real time, turning him into a martyred figure on screen.

Chester A. Arthur (1881–1885) was polished and stylish. Picture him arriving at a televised inauguration in tailored suits, a president as fashion icon.

Grover Cleveland (1885–1889, 1893–1897) was blunt and heavyset, not a natural telegenic candidate. His honesty might have helped, but image would not have been his strength.

Benjamin Harrison (1889–1893) was stiff and formal, his lack of warmth magnified by cameras.

William McKinley (1897–1901) was approachable and trustworthy, a steady figure who might have soothed audiences during turbulent times.

The Progressive Era: Enter the Natural Showmen

Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909) would have dominated television. Imagine him demanding a crew to follow him on horseback, charging up San Juan Hill all over again for the cameras. He would have been the first action-president, blending politics with spectacle.

William Howard Taft (1909–1913) was kind but awkward. The camera would have been unforgiving, capturing his discomfort in ways campaign posters never did.

Woodrow Wilson (1913–1921) was cerebral and professorial. His long lectures might have lost audiences in a medium designed for punch and brevity.

Early 20th Century: The Camera Gets Sharper

Warren G. Harding (1921–1923) was handsome and polished, perfect for the optics of television.

Calvin Coolidge (1923–1929), “Silent Cal,” would not have fared well. Imagine a televised State of the Union where his monotone delivery empties living rooms across the country.

Herbert Hoover (1929–1933) was technocratic and stiff. Under television’s scrutiny, his inability to connect emotionally during the Depression would have been even more devastating.

The Radio Masters Meet the Screen

Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933–1945) mastered radio, but television would have revealed his disability more openly. Still, picture him in close-up during a fireside chat, his voice warm, his confidence unshaken. For many, the screen might have made his strength in adversity even more inspiring.

Harry S. Truman (1945–1953) was blunt and plainspoken. On television, that lack of polish could have looked refreshing, a president who seemed like your no-nonsense neighbor.

Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953–1961) was the trusted war hero, his calm, grandfatherly presence playing perfectly in living rooms during the Cold War.

The Debate That Changed Everything

John F. Kennedy (1961–1963) was charismatic, handsome, and confident, the first true television president.

Richard Nixon (1969–1974) was capable but tense under pressure. His sweaty, nervous appearance in the 1960 debates showed how unforgiving television could be, rewriting his image in the public mind before his words had a chance.

Retelling History in the Glow of the Screen

Now imagine it:

Jefferson and Hamilton sparring under hot lights, Hamilton’s sharp one-liners clipping neatly into thirty-second spots while Jefferson’s winding speeches fall flat.

Andrew Jackson storming off a stage mid-broadcast, demanding satisfaction in a duel before a live audience of millions. Abraham Lincoln leaning into the lens during a fireside address, his words striking directly at the soul of every viewer. Theodore Roosevelt galloping on horseback with a camera crew in tow, replaying San Juan Hill until it became legend.

If television had existed in 1800, the face on your dollar bill might not be Washington’s at all. It might be the man who looked best in the flicker of black and white, the president who understood that history is not just written in words, but etched in images.